The Case of Hypatia of Alexandria

According to legend, Hypatia of Alexandria was brutally murdered in the year 415 A.D.. Notably, there were no eye-witnesses on record nor was there a corpus delicti nor was there any official inquiry or investigation into the supposed homicide. By modern standards this presumptive crime remains unsolved because it is based solely upon hearsay and rumor well after the putative event. Everything about Hypatia’s death, whether in 415 A.D. or any other time, is a mystery. Her alleged murder therefore calls for some forensic analysis to her case.

Forensic science, or just forensics, typically involves many other sciences, such as biology, geology, botany, chemistry, physics and others in the performance of its reconstructions. Historical science, a branch of forensics, generally is much more limited in scope, relying mainly upon partial or intact human records. Most often these take the form of official documents, authored works, biographical writings, autobiographical writings and material artifacts. In this study, we shall consider both written and pictorial representations of Hypatia to determine what they may reveal about the woman behind the legend, as well as about the claims later generations and societies have upon her. Written references are drawn primarily from the definitive study done by Maria Dzielska on sources informing our knowledge of Hypatia. As there are no pictorial records of Hypatia, representations of Hypatia are drawn from artists’ conjecture.

We begin with a description of the popular legend come down to us over 1,600 years. For this we turn to the source favored by students and others looking for a quick information fix, i.e., Wikipedia. Accordingly, “Hypatia, born c. 350–370; died 415 AD often called Hypatia of Alexandria, was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, inventor, and philosopher in Egypt, then a part of the Eastern Roman Empire. She was the head of the Neoplatonic school at Alexandria, where she taught philosophy and astronomy."

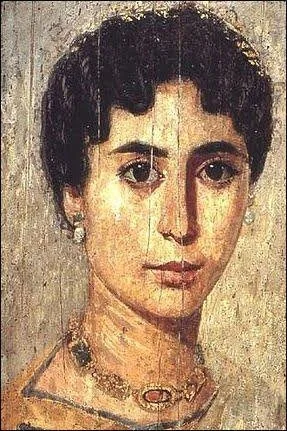

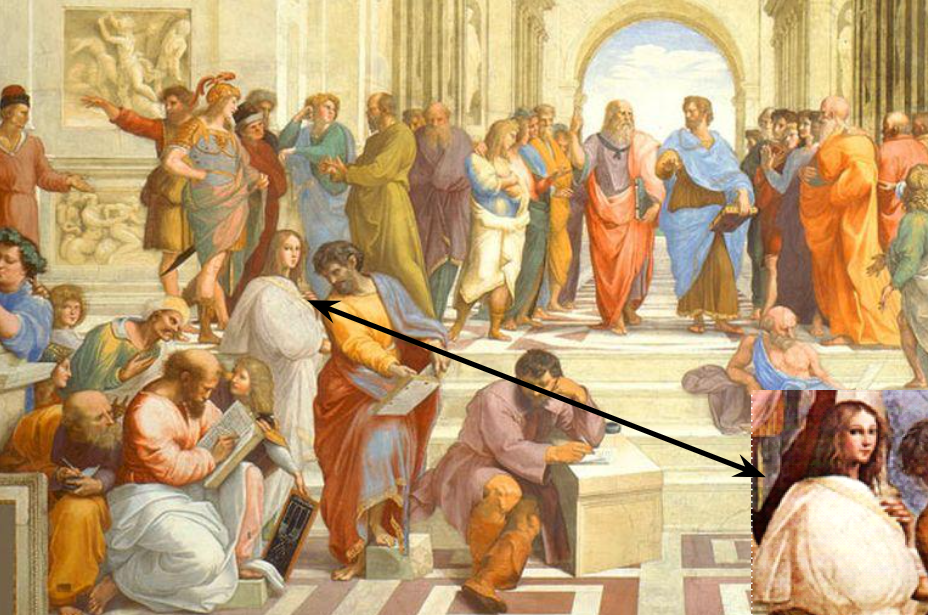

Figure 1 -- Raphael, School of Athens – detail is an

assumed portrait of Raphael's lover Fornarina, once thought to represent

Hypatia.

[Inset and graphic added.]

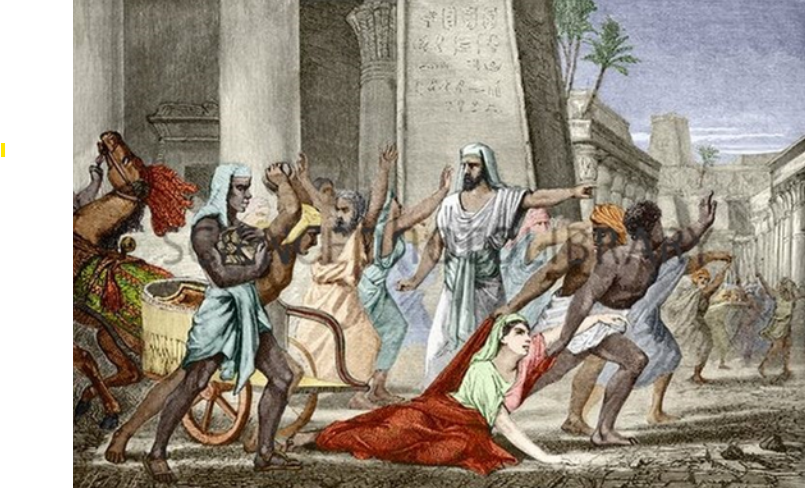

"A pagan, Hypatia was murdered by a Christian mob known as the Parabalani after being accused of exacerbating a conflict between two prominent figures in Alexandria: the Prefect, Orestes, and the bishop, Cyril of Alexandria.”

The past to which Hypatia of Alexandria belongs, i.e., the 4th and 5th centuries of the Roman Empire of Late Antiquity, is to us today a foreign country. We may study written languages and other artifacts from that period, but not living it we remain tourists in a foreign land. Like all sightseers our assessment of long bygone times and places is often subject to our own beliefs and ignorance. The Wikipedia description above is, in fact, rife with both our modern beliefs and ignorance. For instance, the first thing to notice is the uncertainty about Hypatia’s year of birth. Until fairly recently the year 370 had been canonical, though no official birth record supported this. Belief in this date allowed historians and artists to portray her as young and beautiful at the time of her conjectured death. Given the lack of any reference, official or otherwise, to her time of birth, imagination and bias filled in to make youth and beauty a part of her story.